Terra is crumbling.

The blockchain project home to the popular algorithmic stablecoin TerraUSD (UST), which had recently become the fourth-largest stablecoin by market value but now sits at fifth, is near collapse as UST repeatedly fails to sustain its $1 peg and LUNA, the blockchain’s native token, nears zero.

Terraform Labs, the tech start-up behind the development of Terra, halted the production of new blocks on the network on Thursday “to prevent goverance attacks following severe $LUNA inflation and a significantly reduced cost of attack,” it said on Twitter.

A governance attack became less expensive because of the nearly-free price of LUNA – an attacker could cheaply acquire enough LUNA tokens to socially attack the network by forcing a majority vote. (Since Terra relies on a derivation of proof-of-stake (PoS) for consensus instead of hardware and electricity as in Bitcoin’s proof-of-work (PoW), coin ownership equals power. In Bitcoin, the amount of BTC you own doesn’t grant you more power on the network.)

The network went live a couple of hours later as the software patch was released.

This is another important difference between a network like Terra and Bitcoin: while in the former a minority of entities that can vote on things like halting the network, Bitcoin’s true decentralization makes it immune to the whims of any specific group.

How Does UST Work?

Stablecoins are digital representations of value in the form of tokens that attemptively maintain a one-to-one parity with a fiat currency like the U.S. dollar. Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) lead the market capitalization rank and are the most popular and widely-used stablecoins. However, they are issued (minted) and destroyed (burned) by centralized entities that also maintain the necessary dollar-equivalent reserves to back the coin.

Terra’s UST, on the other hand, sought to become a stablecoin whose minting and burning process was performed programmatically by a computer program – an algorithmic process.

Under the hood, Terra “promises” that people can exchange 1 UST for $1 worth of LUNA (whose value fluctuates freely according to supply and demand) at any given time. If UST breaks its peg to the upside, arbitrageurs can exchange $1 worth of LUNA for 1 UST, capitalizing on the premium with an instant profit. If it breaks the peg to the downside, traders can exchange 1 UST for $1 worth of LUNA also for an instant profit.

What Does Bitcoin Have To Do With This?

Terra grew in awareness among the Bitcoin community after Terraform Labs founder Do Kwon said earlier this year that the project would acquire up to $10 billion of bitcoin for the reserves of UST.

The purchases would be made and coordinated by the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG), a nonprofit organization based in Singapore that works to cultivate demand for Terra’s stablecoins and “buttress the stability of the UST peg and foster the growth of the Terra ecosystem.”

While corporate treasury allocations to bitcoin grew in popularity over the past couple of years on the heels of MicroStrategy’s continuous BTC buys, LFG’s move represented the first major BTC allocation as a reserve asset by a cryptocurrency project. The news was met with a mix of enthusiasm and skepticism among the community.

Bitcoin Magazine reported at the time that the algorithmic maneuver employed by the UST stablecoin to maintain its peg was of doubtful sustainability, and the bitcoin purchases did not make UST a stablecoin “backed by bitcoin.” Even Terraform Labs acknowledged that “questions persist about the sustainability of algorithmic stablecoin pegs.”

Terraform Labs also discussed how there needs to be enough demand for Terra stablecoins in the broader cryptocurrency ecosystem to “absorb the short-term volatility of speculative market cycles” and guarantee a better chance of achieving long-term success. This is what the project sought with BTC – create demand for UST by conferring more confidence in peg sustainability.

How Did Terra Implode?

Given the many open questions about the sustainability of such an algorithmically-sustained peg, Terra’s design failed to hold in a period of stress.

As UST began losing its peg to the downside, extra pressure was consequently put on LUNA due to the massive amount of UST increasingly trying to exit and exchange

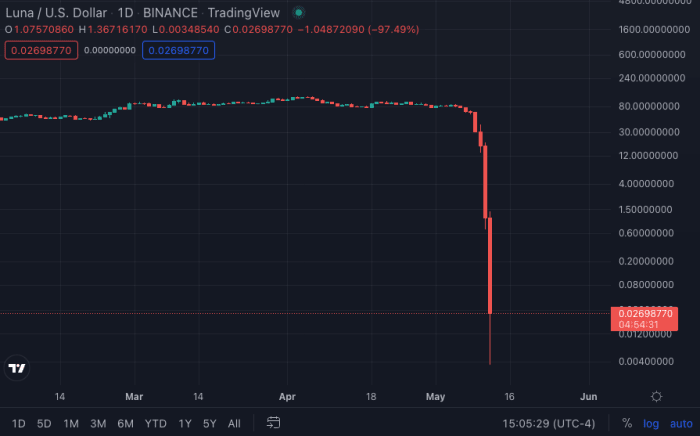

As UST began losing its peg to the downside, traders sought to exit by redeeming each of their UST for $1 worth of LUNA. However, given the fast pace of devaluation, a massive amount of UST tried exiting – more than what Terra was able to exchange for LUNA. That stretched out the on-chain swap spread to 40% and put extra pressure on LUNA, sending its price south sharply.

The token then went down a “death spiral.”

What Does This Teach Us?

In short, it can be argued that the lesson learned from this is: alternative cryptocurrency projects (altcoins) are but an experiment, while Bitcoin is the only tried and tested peer-to-peer digital money.

Bitcoin was born out of the ideals of the cypherpunks, a group of early cryptographers with a shared vision that got together to explore what privacy could mean in the then-upcoming digital world – especially as it relates to money.

The cypherpunk movement was spun out, for the most part, of the work of Dr. David Chaum, a cryptography pioneer that brought the mathematical technology out of the hands of government bureaucrats and into the realm of public knowledge. His explorations kick-started an entire line of work, dedicated to finding how society could port peer-to-peer money – cash – to a digitized economy.

With a clear goal in mind, those mathematicians began crafting what a solution could look like through research and experimentation. Decades later, Satoshi Nakamoto would put it all together and add their own spin to arrive at Bitcoin, the first and only decentralized and trustless form of digital money.

As Bitcoin grew in popularity, alternative forms of what came to be known as a cryptocurrency – a currency that exists in the digital realm through the usage of cryptography – started to be created. While those coins initially were born to compete with Bitcoin, a whole new slew of projects later began to emerge with different value propositions while putting their own spin to the blockchain, consensus and cryptography that made Bitcoin work.

Nakamoto designed the Bitcoin protocol to leverage PoW, a consensus mechanism that relies on computing power and free competition to mint new BTC on Bitcoin’s blockchain. The bitcoin mining race, as it is known, comprises thousands of miners scattered around the world with a single objective – find the next valid block and receive bitcoin as reward.

The altcoins, however, have mostly drifted away from PoW to favor other novel consensus mechanisms. The most popular alternative, PoS, allows participants to lock their holdings of the given project’s native token to become block creators instead of letting them compete with mining hardware and electricity to mine new coins.

While PoW brings real-world costs to miners, costs in PoS are merely digital and represent the amount of money spent to buy those coins being staked. The assumption with PoS is that staking those coins ensures miners have skin in the game and are hence encouraged to behave honestly, but there is no evidence that such commitment is enough of an incentive. Moreover, in cases where a strong devaluation happens as with LUNA, the network risks being hit with a governance attack and may find itself having to take totalitarian actions like halting block production of what was supposed to be a permissionless and unstoppable decentralized network.

The PoW-PoS dynamic is important also because it highlights the experimental nature of altcoins.

Instead of copycatting Bitcoin’s model – a strategy that has been proved unsuccessful time and again – new altcoin projects attempt to “innovate” by copying some parts of Bitcoin’s design and changing up others.

As a result, projects being launched today drift away from most of the ideals underpinning the cypherpunk movement that started decades ago. Such projects call themselves decentralized but for the most part have a founding team that hardly ever drops its controlling position and can steer every decision that happens on the network.

With such a strong desire to innovate, “crypto” projects for the most part end up creating artificial problems that don’t exist so they can invent a novel solution.

Dr. Chaum and the cypherpunks spotted a clear problem in society: How will we have money in the digital age that cannot be spent twice without a centralized authority keeping track of balances? It took decades of research for many specialized scientists and mathematicians of different backgrounds to ultimately culminate in an elegant solution to this problem.

Today, however, cryptocurrency teams take but a couple of years from idea generation to a minimum viable product, not enjoying an organic growth in favor of huge amounts of capital that disproportionately favors insiders at the expense of the regular user.