CNN

—

At 87 years old, Sylvia Earle has no retirement plans. The celebrated oceanographer, who holds the world record for deepest untethered walk along the seafloor, has spent more than seven decades exploring the ocean. As one of world’s most outspoken advocates for protecting it, she’s not ready to stop yet.

“I’m still breathing, so why should I?” Earle tells CNN’s Sara Sidner from the garden of her childhood home in Dunedin, Florida. A day earlier, Earle was out in the ocean with a wetsuit on and a scuba set on her back, searching for new life and fulfilling her enduring curiosity.

She has swum here ever since she was a kid, but Earle insists there’s always more for her to learn. “Every time I go into the water, I see things I’ve never seen before,” she says.

This is even true in the waters off Florida, where development and ecological disasters have marred the coastline and surrounding wildlife. Earle has witnessed seagrass meadows being dredged and filled to make way for waterfront properties; she’s seen the effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, when 168 million gallons of oil poured into the Gulf of Mexico; and in her lifetime, Caribbean monk seals, which could once be seen lounging on Florida’s beaches, have gone extinct.

“It’s nothing like the paradise that I knew,” she says, but some form of recovery is still within reach. “Nature is resilient, that’s cause for hope. But we need to give nature a break, take the pressure off.”

Sylvia Earle: Diving for hope

24:00

– Source:

CNN

In Dunedin, that’s exactly what is now happening. The coastline, stretching from Apalachicola Bay in the north to Ten Thousand Island in the south, was designated a Hope Spot in 2019, as part of Earle’s Mission Blue program, which supports ocean research and restoration. There are more than 140 Hope Spots worldwide, all areas that have been scientifically identified as critical to the health of the ocean and are now being safeguarded by local communities and institutions.

“A healthy ocean begins with awareness,” states Mission Blue’s website, something that Earle has tirelessly strived for. Today, she tours the world, speaking at schools or UN general assemblies and the US Congress, sharing her tales of the ocean and urging conservation action.

Such steadfast commitment to the ocean has earned Earle many titles, from “Her Deepness” and “Queen of the Deep” to “Sturgeon General.” She is credited for opening doors to women in ocean science, becoming the first female chief scientist at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1990, and she has pioneered the use of submersibles for deep ocean exploration.

“There was a time in the 1970s when access to the skies above and the depths below was roughly in parallel, but then the focus on aviation and aerospace took off,” she says. “Until very recently, more people had been on the moon than to the deepest parts of the ocean.”

Submersibles gave scientists like Earle the luxury of time. Scuba diving to extreme depths is very technical and dangerous, and going deeper often means less time at the bottom due to increased pressure and limited oxygen supplies. In a submersible, however, researchers can reach the seafloor and stay there for hours.

Related: In the ocean’s twilight zone, this diver is discovering vibrant new species

During her voyages to the deep, Earle says she would stare through the window, asking questions to marine life passing by: “Who are you? Where did you come from? How do you spend your days and nights? What’s it like to be a fish?”

She hopes that rising back to the surface with this knowledge would help humans understand the value of life underwater and persuade them to start treating it differently. “We measure ocean wildlife by the ton, we don’t even accord them the dignity of how many individual tunas are there,” she explains. “It just shows we don’t regard these as living creatures, as individuals.”

While her message has certainly begun to penetrate, Earle believes that increasing access to the deep ocean and letting people see the life for themselves would help to truly cement it.

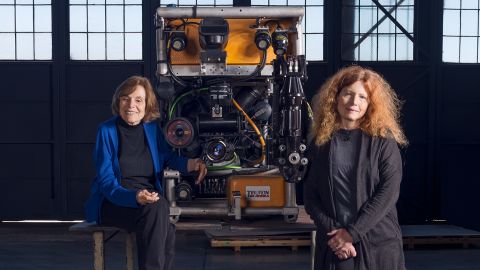

Her biggest goal is to build new submersibles that give ordinary people direct access to the deep ocean, says her daughter Liz Taylor, who is also president and CEO of DOER Marine, a company founded by her mother in 1992 that builds submersibles. “She really wants to be able to pluck individuals from all over the world and have them get that experience with her in the sub.”

Taylor agrees that traveling to the deep sea would help to change people’s attitude towards it. “You really feel that you become part of the ocean around you. The animals are very curious, they like to come over and check you out. (It’s) the reverse aquarium experience.”

When face-to-face with a fish in their own environment, it’s hard not to see them as dynamic and characterful creatures, she adds.

An empathy for all living things runs deep within the family. Taylor says the idea that “all life matters” was ingrained in her and her two siblings from an early age. Earle attributes it to her own mother, who she said had a deep understanding of the “fragility of life” – possibly due to their own family tragedy. Before Earle was born, her parents had lost four children, their first in a car accident, their second from an ear infection, and twins who were born prematurely.

“My mother’s perspective was you want to save creatures for their own sake, they deserve to live,” she says. And as a result, she became the kid “who had cocoons in jars watching the emergence from a caterpillar to a butterfly.”

Related: A shark ‘superhighway’ is being protected by fishermen

This may have been when Earle’s quest for knowledge of the natural world began, but it is yet to abate. After a life spent serving the sea, she believes that understanding nature is key to its recovery.

“I can, in a way, forgive a lot of the terrible things that we’ve done to the water, to the air, to the soil, and certainly to life in the sea … because we did not have the understanding,” but today there is no excuse, she says.

“We’re armed with knowledge that did not and could not exist until right about now.”