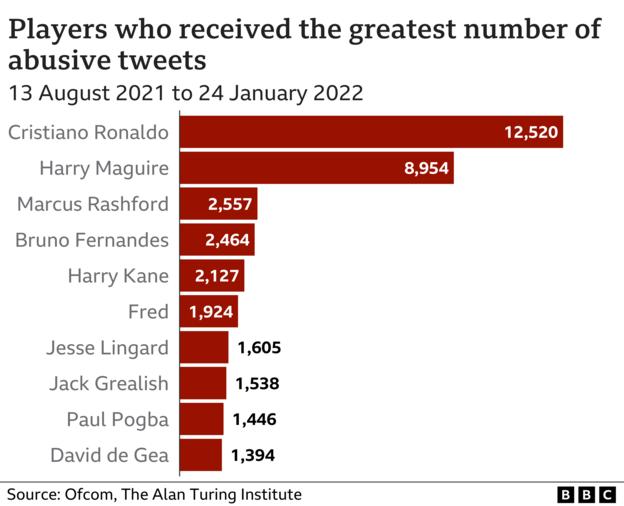

Manchester United’s Cristiano Ronaldo and Harry Maguire have received the most Twitter abuse of any Premier League players, a new report has found.

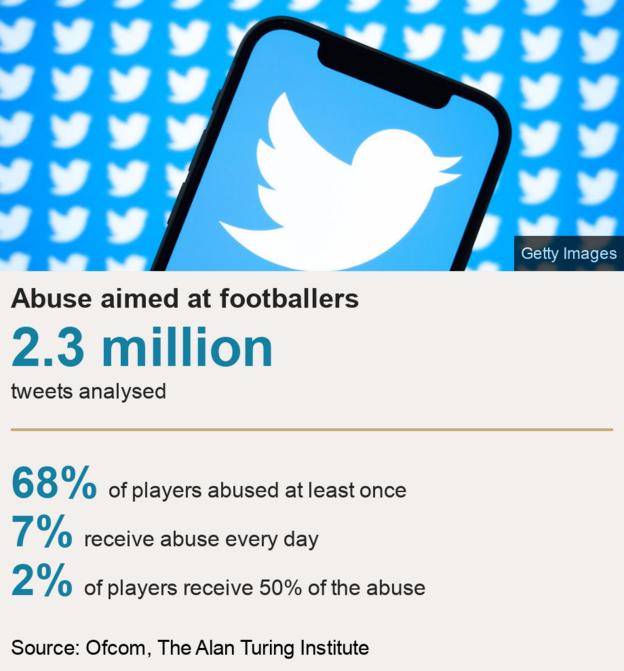

Ofcom analysis of 2.3 million tweets in the first half of last season found nearly 60,000 abusive posts, affecting seven in 10 top-flight players.

Half of that abuse was directed at just 12 individuals – eight from United.

However, the study by the Alan Turing Institute also found the vast majority of fans use social media responsibly.

“These findings shed light on a dark side to the beautiful game,” said Kevin Bakhurst, Ofcom’s group director for broadcasting and online content.

“Online abuse has no place in sport, nor in wider society, and tackling it requires a team effort.”

Ronaldo and Maguire most targeted

The report identified two peaks in the frequency of abusive tweets.

The first came on the day Ronaldo rejoined Manchester United on 27 August 2021, generating three times more tweets than any other day (188,769), of which 3,961 were abusive. At 2.3%, that is marginally lower than the daily average.

The volume of posts can largely be accounted for because of Ronaldo’s 98.4m followers. On this day the Portugal forward was mentioned in 90% of all tweets aimed at Premier League footballers and 97% of abusive tweets.

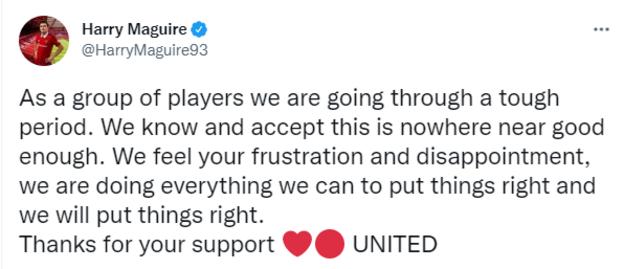

The second peak came on 7 November when defender Maguire tweeted an apology following Manchester United’s 2-0 home defeat by Manchester City.

On that occasion, 2,903 abusive tweets were sent – 10.6% of the total that day – with many users reacting to Maguire’s post with insulting or demeaning language.

The report also found a duplicated tweet – using the same exact phrase – was sent to Maguire 69 times by different users within two hours.

The study says “it is possible that this duplication occurred because users saw the abusive message and decided to replicate it – indicating organic organisation rather than coordinated behaviour”.

The Alan Turing Institute said that understanding the organisation of online abuse is of increasing interest given the harm caused by co-ordinated attacks and “pile-ons”.

Other players were targeted by large volumes of abuse following a “trigger”, despite receiving relatively few tweets overall.

Newcastle defender Ciaran Clark, now on loan at Sheffield United, was sent off against Norwich in November, with 78% of the abusive tweets he received coming on this day.

Meanwhile, Crystal Palace’s James McArthur was also the subject of a spike in abuse after being yellow carded for stepping on Bukayo Saka against Arsenal in October.

Researchers will also look at whether a spike took place when an incident that saw West Ham defender Kurt Zouma kicking and slapping his cat came to light, as that took place after the data was collected.

How did the study work?

As part of its preparation to regulate tech giants under new online safety laws, Ofcom teamed up with the Alan Turing Institute, the UK’s national institute for data science and artificial intelligence, to analyse more than 2.3 million tweets directed at Premier League footballers over the first five months of the 2021-22 season.

The study created a new machine-learning technology to automatically assess whether tweets are abusive, while a team of experts also manually reviewed a random sample of 3,000 tweets.

Of that sample, 57% were positive towards players, 27% were neutral and 12.5% were critical. The remaining 3.5% were abusive.

Of the 2.3 million tweets analysed with the machine-learning tool, 2.6% contained abuse.

“These stark findings uncover the extent to which footballers are subjected to vile abuse across social media,” said Dr Bertie Vidgen, lead author of the report and head of online safety at the Alan Turing Institute.

“While tackling online abuse is difficult, we can’t leave it unchallenged. More must be done to stop the worst forms of content, to ensure that players can do their job without being subjected to abuse.”

What are the recommendations?

The UK is set to introduce new laws aimed at making online users safer, while preserving freedom of expression, with rules for sites and apps such as social media, search engines and messaging platforms.

“Social media firms needn’t wait for new laws to make their sites and apps safer for users,” said Ofcom’s Bakhurst.

“When we become the regulator for online safety, tech companies will have to be really open about the steps they’re taking to protect users. We will expect them to design their services with safety in mind.

“Supporters can also play a positive role in protecting the game they love. Our research shows the vast majority of online fans behave responsibly and, as the new season kicks off, we’re asking them to report unacceptable, abusive posts whenever they see them.”

Twitter says it welcomes such research to help improve conversations on its platforms, while also pointing to a number of online abuse and safety features it has implemented to stop such posts reaching individuals.

A Twitter spokesperson said: “We are committed to combating abuse and, as outlined in our Hateful Conduct Policy, we do not tolerate the abuse or harassment of people on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity or sexual orientation.

“As acknowledged in the report, this type of research is only possible because our public API is open and accessible to all. However, our publicly-accessible API does not take into account the range of safeguards we put in place, so this does not completely reflect the user experience.”

Twitter said it had not seen the data, but claimed 50% of all “violative content” is found by its own processes to help the burden on an individual to report abuse, adding “we know there is still work to be done”.

European football’s governing body, Uefa, last month pledged to work with social media platforms to tackle online abuse as part of a Respect campaign during the European Women’s Championship.

Other projects have included BBC Sport’s Hate Won’t Win campaign, alongside Sky Sports, while in April 2021 football clubs, players, athletes and a number of sporting bodies undertook a four-day boycott of social media in an attempt to tackle abuse and discrimination.